Becoming a better shooter is something we are always striving for. To learn more about fundamentals, we recently sat down with Ian Tashima, a well-regarded expert on the topic. In part two of our recent discussion, we discuss the importance of stability, factors that impact your performance, parallax, zeroing misconceptions, and more.

Background on Ian via the Lethality Ranch website:

Ian Tashima spent eight years in the Marine Corps as an Intelligence Analyst, and a further 11 years in the Army National Guard as an Infantryman and Civil Affairs NCO. During the Global War on Terror, Ian voluntarily deployed to Afghanistan three times and once to Iraq. Further assignments & duty positions include Combat Advisor (ETT & SFAT), Tactical Electronic Warfare Specialist, Counter Radio Controlled IED Electronic Warfare NCO, Anti-Terrorism Officer, senior small arms trainer, Assistant State Marksmanship Coordinator and Program Manager for the Designated Marksman, Small Arms Firing School, and Unit Marksmanship Trainer Courses…

Q: Are there fundamentals that we should be working to improve our fundamentals and become better shooters?

Ian Tashima – When it comes to becoming a better shooter, there are base, critical skills that we need to group, zero, and engage targets effectively. Stability in our position, aiming while accounting for variables, control of the weapon, and moving into and out of positions are essential functional elements in this process. Starting at square one, You must be able to get as stable as possible to make the needed shot.

For zeroing, I prefer to prone out on the ground and recommend employing stability aids such as a pack up front under the free-floated handguard, and a shooting bag at the rear. That said, I know some people do very well with a shooting bench…a proper shooting bench like the ones made of concrete, not the portable folding kind, which can still introduce wobble. Regardless, getting as stable as possible is critical. All of this supports the reality that zeroing is merely calibration of your weapon and sighting system. Hence, you need to remove as many variables as possible.

Becoming A Better Shooter – Shooting Mechanics

The next thing to focus on is your shooting mechanics, which includes your body position behind the gun. This is where things can start to go off the rails. You might have the buttstock on your shoulder, but you aren’t getting a tight contact with it. I often have students place their finger between my rifle buttstock and shoulder to demonstrate the kind of shoulder pressure I employ.

Most of the time, newer shooters are a little surprised at how much pressure my shoulder contact brings. When shooters aren’t mounting the gun effectively, you can easily see it in the way the gun moves under recoil, with excessive movement. You cannot just let it touch your shoulder and be happy with that. There has to be pressure there, where it feels like you are controlling it. Becoming a better shooter means you have to build some inherent structural stability, so getting your shoulder involved is important.

From there, other things are essential, like trigger finger placement, and resting the magazine on the ground if you have a non-floated barrel. If you have a floated barrel, then getting a bag upfront can be key for stability.

Your rifle’s aiming components now come into play. As we discussed previously, magnified sights won’t help you in becoming a better shooter , but they will help you see better.You must aim at the same spot for every shot, on your zeroing target. Magnified sights enable you do precisely this.

You can also do very well with a red dot, but some people do have issues with their eye, perhaps age-related, but some precision can be lost. So, having a hardware item to compensate for bad eyes definitely can help. Regardless, you have to aim at the same spot. I know that might sound basic, but that point is sometimes lost on newer shooters

Becoming A Better Shooter – Choose Your Targets Wisely

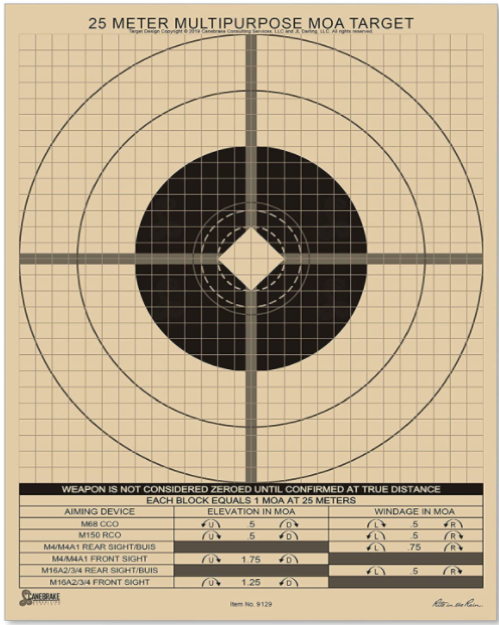

This brings us the zero target, itself. Some targets are better than others. You will find that some targets have a very finite, repeatable aiming point, while others are just a nebulous black blob, like the old Army zero target, which was a silhouette of a person, versus the new, current one, which is a bullseye with a neat, little diamond in the middle that provides a highly repeatable spot. That diamond’s dimensions were specified to benefit both 2 MOA red dots and the older 4 MOA red dots.

Suppose you are not aiming at the same spot every single time. In that case, you cannot know if your group size is attributable to your skillset, the weapon and ammo capability, or aiming at a slightly different spot for each shot. Removing each element of “slop” is important, and is very much akin to “tolerance stacking.” A good zero target helps with this.

So, now we have the shooter, the target, and the hardware elements. Now, being able to work the trigger and keep the sights on target is critically important. Shooting is simple…putting the sights where you want them, and pressing the trigger without moving the sights. The problem? Just because something is simple does not make it easy for the uninitiated.

Q: So, what are some things our readers can do to become a better shooter?

Ian Tashima – There are some commercial, off-the-shelf items like the MantisX. It is a fantastic product that is brutal in its honesty, its assessment, and its feedback. It tells you precisely what your stability and control is immediately before the shot, precisely when you fire, and then immediately after the shot for your follow-through. These “stages” of pressing the trigger are perfectly aligned with US Army training doctrine’s “shot process,” by the way. I find that having this kind of feedback is critically important since being able to aim at the same spot for each shot, while being as stable as possible, is critical. The MantisX supports dry-fire practice, as well as live fire, so when ammunition is scarce or your ability to get to a shooting range is limited, you can get solid repetitions to make needed improvement. Combine the MantisX with a trigger resetting device like the Mantis Blackbeard, and you have a great combination that develops solid skills.

Another imperative is to not start zeroing until you can demonstrate the ability to fire a good group size. Without that, you do not know exactly where your barrel is pointed. If you begin prematurely adjusting your sights based on sloppy data, you don’t know what you are trying to adjust off of. You’re trying to zero based on a bad group. If you are doing that, are you actually zeroed?

So, try to get no more than a 6 Minute of Angle group, which is a pretty loose standard, and then begin adjusting your sights. With a 6 MOA group, you have the shooter mechanics to get hits on bad guys out to 300m, disregarding environmental influences (wind direction, wind speed, altitude change, angled fire) and target complexities (speed and direction of movement, degree of exposure, time of exposure, high angle engagement, etc) . If not, you’re allowing a “failure cascade” to continue.

In short, the failure cascade is as follows: bad knowledge -> bad stability -> bad mechanics -> compounded by bad zero target -> less than ideal sighting system -> leading to bad group size -> bad zero, and on and on.

Q: Can you discuss the importance of head position?

Ian Tashima – Simply, it comes down to consistency. Furthermore, a good head position provides another contact point for stability. Parallax can also come into play.

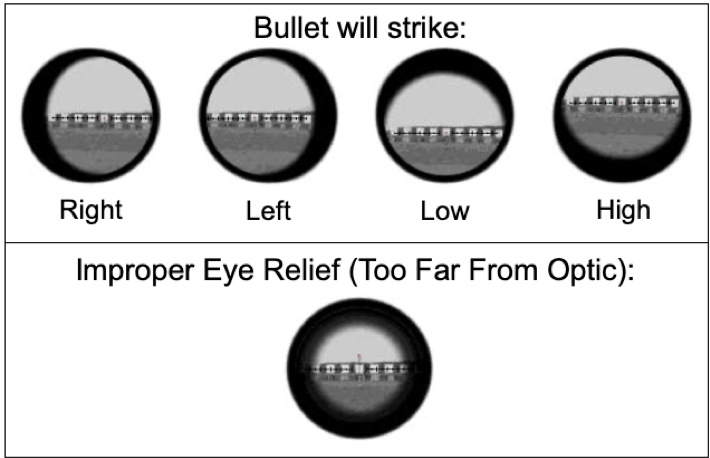

Parallax is a perceived shift in where you are aiming, when you move your eye position behind the optic. If there’s a perceived shift in the reticle’s aiming point and your target, when your head or eye moves position, that’s parallax. With a magnified optic like an LPVO, it’s extremely important to know that this parallax exists. Thankfully, with magnified optics, there is some quick feedback that will tell you if you’ve got your head and eye position in a bad spot. Look for scope shadow, meaning a dark, shady area within your field of view. Shift your eye position around, or move it front or rearward relative to the ocular lens until you’ve got a full field of view from top to bottom and left to right.

If your optic has a parallax knob, also ensure that it is adjusted correctly. Play with it until you can move your eye position around and not see a perceived shift between your target’s aim point and your reticle.

Q: You touched on it briefly, but what does it mean to zero rifle, and are there misconceptions that we should be aware of?

Ian Tashima – First, zeroing is just calibration. Often, especially in the military, people confuse zeroing with “training.” It’s not training, it’s just a maintenance check. A lot of salty old-timers in the military believe folks need to be in fully body armor and helmet, when zeroing. This isn’t the case. Do mechanics need to were those things when performing a wheel alignment on a tactical vehicle? Of course, not. It’s the same thing.

Next, something that gets a lot of debate is “what is the best zero distance?” To me, this goes back to the question of “what is your operating environment?” Are you a rancher that has to protect livestock in open space, at longer distances? If that is the case, your zero distance might be farther out so that you can engage without having to worry about trajectory, as much. If you are worried about your home defense gun, and you are in an urban environment, I would probably look at a different zero than what that rancher would have.

But really, no matter the sight’s zero distance, as long as the shooter knows what their bullet is doing in flight (external ballistics), and is practiced in applying holds at various distances, the zero distance doesn’t matter as much as people like to get worked up about it. Granted, some zero distances are optimized for certain environments, but it all comes down to knowing your gun/cartridge combination. And by the way, applying precise holds at longer distances is enabled by having a magnified optic.

Becoming A Better Shooter – Zeroing Misconceptions

A misconception people have is that they are finished zeroing when they have fired their last shots at 25m for a 300m zero, or at 50 meters for a 200m zero. If anything, they have completed just one step in the zeroing process. Unless you shoot at whatever true distance you choose (100, 200, 300 meters), and unless you confirm where that bullet is, relative to your line of sight , and it crosses your line of sight that second time at your chosen true distance zero, you are not finished zeroing. Everything you have done at a close distance was just preparation.

Sometimes, it’s good to start with a laser boresight at 10 meters (using a proper laser offset) to ensure that your rounds will strike on paper at a distance of 25 meters (or 50 meters). Then at 25m or 50m, fire 5-round shot groups to ensure your rounds are striking where they ought to be, while using the correct ballistic offset, if needed (a slight difference between your point of aim and the bullets’ point of impact). Finally, go to your true zero distance to confirm.

So, for example, if I want a true-distance zero of 300m with a 14.5” barrel and I’m shooting M855 ball ammunition, I might want to conduct a 10m laser boresighting to have a 1.6 cm (.55”) offset. This will ensure that my rounds are striking my target at 25m and are reasonably close to where I need them.

Next, I want to fire groups at 25m and adjust my sights so that my 5 round shot group is centered and about 2 MOA below my point of aim. This ensures that my rounds will strike my target at 300m, and are pretty darned close to my point of aim. If my sights need elevation adjustment, because I’m high or low, I’ll make that change. Ideally, I’d also fire groups at 100m to get my windage setting dialed in and validated, so as to remove wind deflection as a variable, at farther distances.

Q: You mention wind deflection…Can you address the role of wind in zeroing? Is it something to be concerned with?

Ian Tashima – You should confirm windage adjustments no farther than 100 meters. At distances farther than 100m, wind will become a variable, and can sometimes be difficult to account for. I say no farther than 100m, because even with a 10 MPH full-value wind, and a standard Mil-spec M4 and ball ammo, that wind will only deviate your shot by about an inch, so it’s really negligible. You can make good solid windage and elevation adjustments. Past that, leave your windage alone, and at true distance, only adjust your sights for elevation so bullets are hitting at the right spot, up and down. If there is deviation left and right past 100, that’s likely either you, or the wind…but regardless, don’t touch windage past 100. Just adjust elevation.

Something I’ve been advocating for, but which isn’t often done, is to come back to 25m and shoot a five-round shot group to actually see where the rounds are supposed to strike at 25 meters, for your chosen true-distance zero. In other words, spend some time to find out what that weapon/ammo/sight combination ballistic offset truly is. Perhaps you have to take your optic off for maintenance or repair, and when you remount, you don’t have access to your true distance range anymore and only have access to a 25-meter range. How can you be sure that your weapon is still properly zeroed? You can be certain, based on solid data, what the offset is supposed to be based on known-good information. Collect that data for future reference.

Q: So, just to reiterate…when it comes to a 25/300 or 50/200 zero, it really comes down to what our needs are, versus copying what someone else is doing, correct?

Ian Tashima – If you solicit the “best” this or that, and the response doesn’t include soliciting further specific use-case information, you’ll get a response that is based neither on your environment nor your mission. You’re getting an answer without relevance.

One person you ask might be a casual weekend plinker. The other person you ask might be more of a long-range precision shooter. If they both give you what they think the best zero distance is for a rifle and don’t consider that you live in an urban environment, for example, their answers would be irrelevant. The same goes for equipment and gear. It does not matter what they are using. You don’t know their mission. Their mission or use case might not be the same as yours.

I also need to point out that only very specific gun/ammo combinations will actually provide a 50m/200m zero. Most systems will not yield a 200m true distance zero, when POA=POI at 50m. Many people are surprised to find that their 50m zero results in bullet strikes higher or lower at 200m.

Q: I’ve been at the range, and things were not going expected, but I didn’t know how to address. What do we do in that situation vs. wasting ammo and hoping things work out?

Ian Tashima – Always keep in mind what Vince Lombardi advocated: “brilliance in the basics.” The man is recognized as one of the greatest coaches ever, in athletics. He probably knows a thing or two.

Start with the easy things first. Ensure your weapon is good to go. Make sure that your sighting system is mounted correctly and it is tightened down. Putting witness lines on knobs and screws is a good idea so that you can quickly tell if they are coming undone in the future. I’d recommend making sure your barrel nut is tight. Grab hold of your upper receiver with one hand, and grab the barrel with the other, twist it, and make sure it is not loose. I was once given an M4 straight out of maintenance, and it had a loose barrel nut. It took me forever to realize why my groups were terrible, and the whole time I was going crazy.

Another thing to consider is that maybe you are just having a bad day. Take a break, drink some water, or come back later. I’d rather not waste rounds on bad reps. Stop and come back when your head is right. Maybe something is going on that is distracting you.

After that, know that there are shooter’s checklists out there. Ensure you have a good stable position. Perhaps don’t amp yourself up on energy drinks or coffee ahead of time.

Get your natural point of aim. Remember the importance of good trigger control. Use natural or artificial support to make sure you are as stable as possible. Make sure you are not rushing. You don’t need to get things done quickly…you want to get things done the first time correctly. What we’re doing is simply calibration. If you don’t have the hardware or mindset to get something properly calibrated, it’s probably best not to bother until you are more prepared.

###