Duane Liptak – Magpul Industries – AR-15 magazines have come a very long way since the introduction and adoption of the M16, as have many developments in chamber spec, gas pressures, materials, propellants, and design tweaks to the original operating system. Basic expectations for fighting rifle performance had traditionally been 500 mean rounds between stoppages (MRBS) for the system in clean environment TOP 03-02-045 testing.

Even though that performance standard had been left by the wayside for several decades, these numbers have only recently come up for discussion to be changed. This is due to the prior standard being made laughably irrelevant by current performance capabilities.

The most recent round of US government testing of the GEN M3 PMAG at Aberdeen resulted in well over 30,000 rounds between magazine-related stoppages and over 12,000 MRBS for any causes. Yes, that’s 12 cases of ammunition between stoppages with a direct impingement system. The M2 PMAG isn’t far behind that.

So…how did we get to that point? What are the characteristics of a magazine that can achieve that level of reliability? I get asked that a lot, and so here’s an attempt at explaining some of that.

As a Magpul employee, I have some level of bias. I could write several thousand words on why everyone should use PMAGs, backed up with facts, and test data. This is because I absolutely believe in the product, and the data does speak for itself. But, in the interest of some level of objectivity, I’m going to back out a level and talk about the factors in making a good magazine in general, which will hopefully provide some useful takeaways.

Again, I believe the solutions, geometries, materials, and characteristics of the PMAG are superior, or I wouldn’t work here, and I won’t try to hide that, so bear with me. Also, please note that this article isn’t the whole story. As you might imagine, I, and more importantly, the full design and engineering department at Magpul, could “nerd out” on this stuff for days. However, if I do that here, I know it would make for a pretty dry read.

So as you read, please understand each subsection in this article is just a scratch of the surface. I’ll attempt to hit the highlights in a readable format while not getting into anything that we’d consider trade secrets.

AR-15 Magazine Basics – What Does the Magazine Do, Exactly?

The best place to start in defining magazine performance is understanding what we expect a magazine to “do.” A magazine, to be useful, must:

Present a supply of cartridges into feeding position, in all compatible platforms, that are in an “acceptable” orientation with respect to the chamber, feed ramps, and bolt face; must provide an acceptable amount of resistance to stripping the top cartridge forward by the bolt; must provide a stack rise time for the top round to be fed upwards into a stable feeding position, resting on the feed lips quickly enough to accommodate the fastest acceptable bolt speed of the host firearm—and must maintain consistency in these variables across the range of atmospheric and contaminant conditions, and after rough handling within variation that is acceptable to the host firearm.

Easy, right?

Yes, that’s a mouthful, but still doesn’t get to the “how” and to the practical criteria that we can demonstrate in choosing magazines, cutting through at least some of the “magazine nerd” stuff. So, let’s break down how all that is supposed to work and put it in some practical terms.

AR-15 Magazine Basics – Presentation and Stack

The presentation is king. Positioning the top round in the stack correctly to support the feeding stroke of the bolt carrier is where the “rubber meets the road” in magazine performance. Ideally, we want to present the round in a fashion that will allow it to travel as straight into the chamber as possible.

Every surface the round touches and every angular deviation it must make in its path robs energy from the bolt carrier that might be helpful in closing and locking the action when fouled or dirty.

While ideally we’d like to place the round directly inline with the chamber for best feeding, the presentation height has to be low enough to allow the bolt to travel rearward over the top of the stack to allow function.

This is where feed ramps come in. They help guide the cartridge up to the appropriate height to get into the chamber—we just ideally want to impact the feed ramps as little as possible to preserve that energy. And so…we can just set our feed lips up to point the cartridge directly at the chamber, and all is well, right?

Well…not exactly.

If you set a presentation angle arbitrarily without a proper round stack/follower underneath providing enough stability to the top round, it will nosedive if unsupported in the front. Or, it will go bolt over base if unsupported in the rear. Slow or uneven stack rise (rounds pushed up by spring/follower) can also create these conditions if the round is not stable and supported on the feed lips by the time the bolt travels forward.

Straight magazines for tapered rifle cartridges provide this support with an articulating or semi-articulating follower and biased magazine spring to give the desired support. The follower has to be able to “rock” a bit to accommodate proper support as the magazine empties, and the follower travels up. You can’t have a TRUE “anti-tilt” follower in a straight magazine to feed tapered cartridges, or at least to feed them well.

With a straight magazine, there are limits to how many cartridges can be accommodated in this fashion. The cartridges naturally want to form a curve when stacked. At a certain point, the articulating follower and spring method can’t keep up, and the mag body also limits stack geometry.

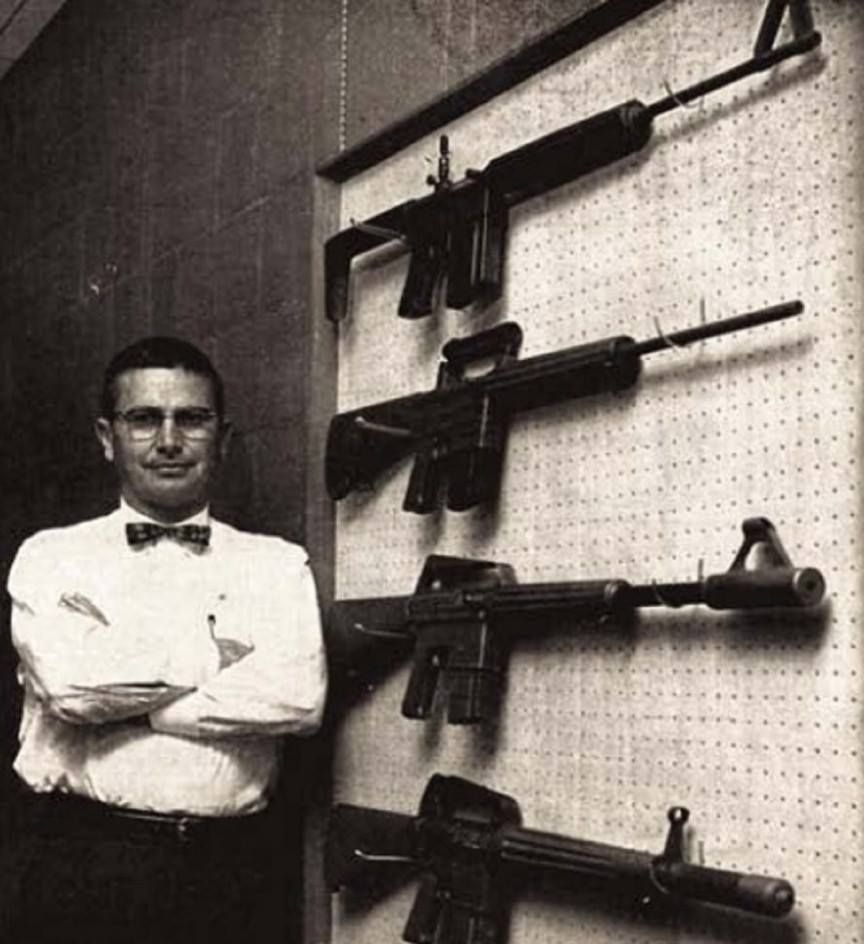

The feed lip presentation angle is also limited by this geometry. If you try to present at too high of an angle, it complicates the support problem, and at a certain point, the follower and spring can’t keep up. Eugene Stoner was a damn smart man. With stamping technology and straight magazine bodies, Stoner settled on a presentation angle that relied a good deal on the feed ramps, but that could be supported by the follower and spring. This worked fairly well.

But what if we want more cartridges in the magazine? For the best function, the answer is to curve the magazine. Due to the combination of straight mag well section in the M16 and limitations of stamping at the time, the USGI 30-rounder used a “dogleg” curve. This accommodates the curve of the cartridge stack far better than a straight magazine, but it’s a compromise.

We still can’t have a 100% anti-tilt follower. Some follower articulation is required to navigate the changing curve radius inside the magazine, but we can get closer. There are also inconsistencies in stack support created by the follower navigating the curve, which can manifest in an increased incidence of stoppages between rounds 14 and 24 in the stack or thereabouts. This is especially true when the magazine is dirty.

There are also still limitations on the presentation angle that can be supported. Ideally, we would want something very close to a “constant curve,” described by the radius of a circle created by the tapered rifle cartridges. This allows a true anti-tilt follower and permits support of the round stack at higher presentation angles by properly arranging the stack. Polymer magazine bodies generally allow the closest approximation to a proper, “perfect” round stack in the AR platform.

We also need to have enough space laterally for the rounds to stack perfectly in that orientation. This means the rounds nest together in an alternating fashion, where each round contacts four other rounds surrounding it. This nesting allows rounds to be pushed straight up without tangential pressures (rounds that don’t nest properly are pushed outward as they are pushed upwards), increasing the drag of the round stack on the magazine walls.

We also want some room for ribs. Ideally, rounds should only contact the magazine walls at a few points (ribs) to minimize drag and provide room for grit and fouling to pass. This is why trying to shoe-horn rounds with a larger case head diameter than 5.56/.223 into the AR mag well generally doesn’t work that well. This forces a compromised lateral stack, increasing pressures on the side walls. Raising spring pressure to apply more vertical force to overcome that also increases lateral pressures, increasing drag. Then, we’re off to the races of unintended consequences and a parade of stoppages created by poor stack rise.

AR-15 Magazine Basics – Pushing the stack

Once properly arranged, we have to apply force to the round stack to continue putting the top round in the appropriate place. This brings us to the spring.

Spring rate, design, materials, treatment, and finishing is a broad, complicated subject. Suffice to say that we have to design a corrosion-resistant spring with an appropriate coil angle to apply the right bias to the follower to work with our follower design and stack geometry, and our follower has to transfer that spring force consistently as the stack rises/depletes with the operation of the firearm.

If you don’t properly design and constrain the spring path, you can get all sorts of weird spring force changes throughout stack travel. This destroys our chances for consistency in presentation, regardless of geometry.

We also have to, or at least should design the spring to allow full capacity without reaching a “solid” state, where all the coils touch. Compression to a solid state can reduce spring life. Prevention of solid state is ideally managed by follower/lockplate or follower/floorplate contact.

We designed the body, follower, and spring in PMAGs to allow closed bolt insertion of a fully-loaded magazine in most ARs without bottoming out the limit of travel and creating high insertion forces. That said, variations in BCG, mag catch, mag well, ammunition specs, and other factors may affect this. It’s a performance characteristic worth checking with your rifle and ammunition.

Some have tried to provide consistent spring force through progressive rate springs. However, it’s important to remember that as our stack increases in size/number of rounds, it increases in weight and decreases in weight as rounds are fired.

A standard rate spring can be designed to increase in spring force under compression at a rate that keeps stack rise consistent, which is more important than the spring force itself. So, in almost every case, a properly designed standard rate spring will be beneficial unless trying to band-aid design deficiencies elsewhere.

I’m seeing a greater understanding lately in online discussions that springs don’t wear out from remaining compressed, and that’s refreshing. A PROPER spring only wears out through repeated cycles. You would shoot out dozens of rifle barrels using a single PMAG before the AR-15 magazine spring became a limiting factor or a wear item from cycling. You can leave them, and any good mag, loaded indefinitely with no ill effects. So, don’t worry about swapping mag springs.

I will caveat the above by noting that there certainly are magazines on the market with bad springs. Poor design, poor heat treating, and other factors can indeed allow a spring to fail while remaining compressed. My advice to you is not to buy mags from anyone who doesn’t understand springs. If you do this, I am confident you will never be an issue.

Magpul PMAG M3 5.56 30RD

AR-15 Magazine Basics – What is it Made of?

This opens the can of worms that brings out strong opinions on all sides of the issue, so we’ll start by talking about ideal properties for a material to make a magazine. First, understand that choosing material properties for magazine performance is a balancing act. There are tradeoffs no matter how you execute it.

Rigidity, or a degree of it is required to maintain correct presentation geometry across temperature ranges and over time with the AR-15 magazine remaining loaded. The material must resist deformation during rough handling, or if deflected, must return to the original geometry. Soft/malleable materials and even “tough” materials can allow deflection, changing feeding geometry, which is very bad. 30 thousandths of an inch of deflection in an AR magazine feed lip can drastically affect the reliability of that magazine but would not be immediately visible to the naked eye.

Energy absorption and distribution through design and materials help soak up impacts. Some materials can also help “settle” the round against the feed lips after stack rise. Once again, materials must be chosen with an eye towards performance across all relevant temperature ranges.

“Resilience” is the descriptor we like to use in balancing rigidity and toughness/energy absorption, meaning we want a material that resists deflection under normal forces. If it receives stresses greater than that limit, it RETURNS to its original geometry. Think springs in this respect.

Surface hardness is another factor. Soft materials that perform great in drops can embed grit and slow stack rise, killing AR-15 magazine performance. Anodized aluminum and nitrided steel are two surfaces with excellent surface hardness, at the expense of other categories. With polymer, it’s easy to choose a softer material that won’t break. However, if you want resilience and surface hardness to prevent deflection of feed lips, and to be able to operate in a dusty environment where grit and dust are a threat, then soft, malleable materials are a disaster. That said, they do make for excellent drop test videos.

No matter what we use, at some point, there are limits to the material capabilities. Ideally, those limits exceed the forces normally experienced by a magazine. For that, we generally defer to TOP 03-02-045 or NATO D14 standards, and 5’/1.5m drops from -60F to +180F, mainly in-gun for the test standards. However, we also do a lot of drops in all orientations of just the loaded AR-15 magazine.

When impacts exceed those forces or are repetitive enough, what is the mode of failure and the indication that it has occurred?

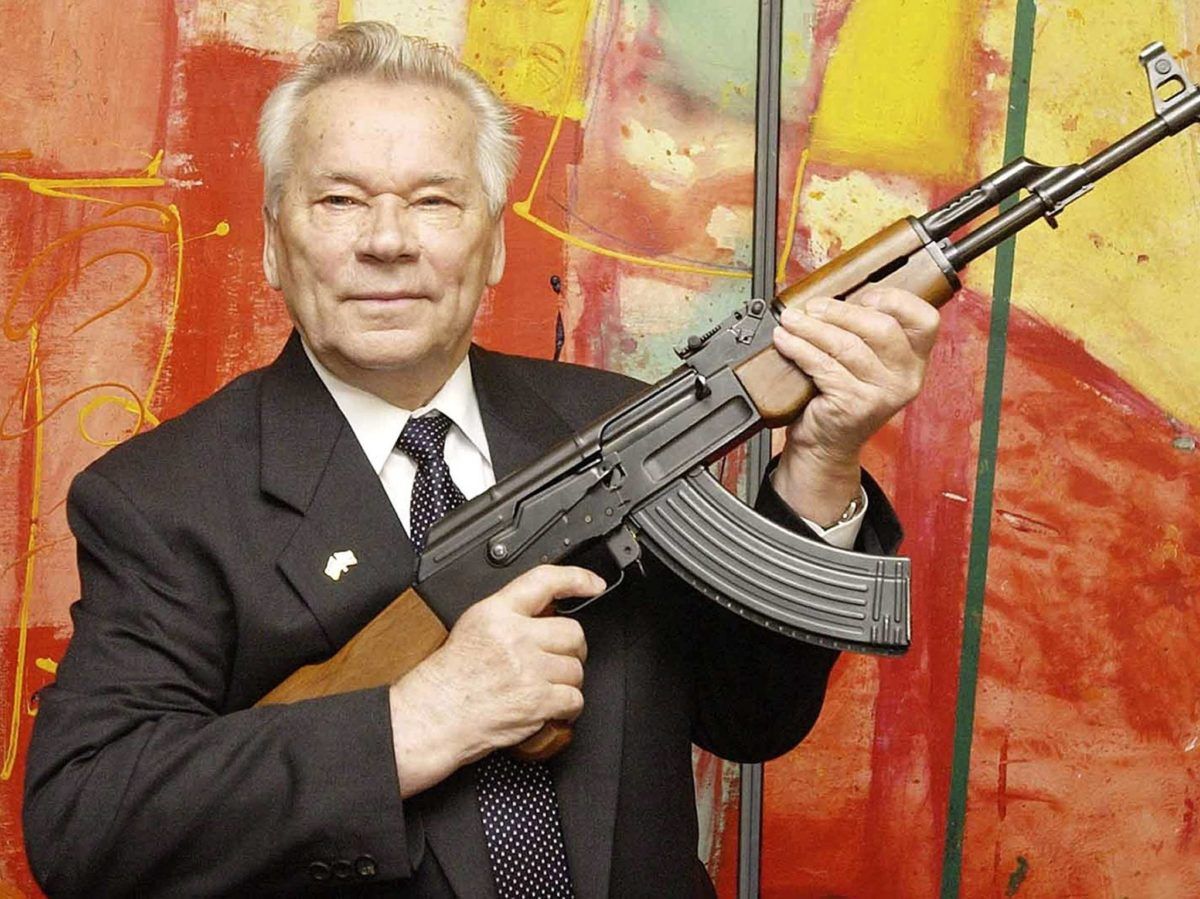

Bent/deflected feed lips can be insidious and not readily visible, as can body damage that can bind a follower in a metal magazine. This is the soviet mindset model with the AK magazine. Bent feed lips or bodies with some degree of malleability, whether metal or metal-reinforced polymer, can be bent back into something approximating a correct geometry.

The AK is somewhat more tolerant of some deviation in feeding geometry than the AR. The mindset of keeping a rifle running, at least passably, without resupply, was likely deemed more important than pure reliability numbers.

In the AR, that model doesn’t work as well. As a young LCpl a few decades back, it was a mystery how out of a group of USGI magazines that appeared identical and unmolested, there would be one or two that just wouldn’t feed right. The deviations that can affect feeding in the AR are so small as to be hard to detect without the military issue feed lip gauge that no one uses anyway. So, what is the alternative?

Ideally, we’d find something to make AR-15 magazines out of that completely resisted deflection, but given the available space and geometry considerations, that material doesn’t exist. It’s absolutely easy to build a magazine that fits in an AR mag well and will pretty much never break by allowing bending or deflection in either polymer or metal, but the need to maintain or return to feeding geometry, and all of the other desired properties (dimensional stability/creep resistance, surface hardness, etc.) are at odds with that model, and make for a magazine-shaped object with less than desirable performance.

A Note on Hybrid Construction

Hybrid construction has been used as a way to try to bridge that gap in various platforms, with metal reinforcements coupled with softer polymers. It’s something we looked at and discarded early on, as polymers with good rigidity and surface hardness to resist dust in the wall thicknesses available in the AR-15 magazine well generally are too rigid to resist separation in the mechanical interface between components, and softer polymers end up with grit performance issues, and failure of the interface/alteration of geometry due to smearing, plus the metal areas suffer from the same deflection concerns as all-metal magazines.

The leading examples of this type of construction in AR-15 magazines finished a distant last place behind 2 generations of USGI magazine and the winning GEN M3 PMAG in USMC testing with both M855A1 and legacy ammunition. Still, some like the idea behind this hybrid method of construction.

The path Magpul arrived at was to aim for that idea of resiliency. After much material research and many thousands of dropped magazines. We strive for a magazine that resists deflection but returns to proper geometry after any deflection occurs. Suppose forces are encountered that go beyond performance thresholds. In that case, cracks may appear, but the magazine will return to correct geometry and generally work until the opportunity to replace occurs.

You can take a PMAG and crack the back spine all the way down to the over-insertion stop, and then hold it together long enough to load it and get it into the mag well, and it will run just fine. Previous military test protocols, leftover from when metal was the only possible choice for magazines, have considered cracks as a failure, regardless of function after the drop.

When FUNCTION and actual reliability after being dropped is the criteria, metal and hybrid magazines fare quite poorly, whether in or out of the weapon system when dropped. Bent feed lips, damaged mag catch slots, or lower rear corner areas that bind the follower and spring, not to mention severe susceptibility to side impact damage, were all things we saw as undesirable metal characteristics. This reality drove the development of the PMAG drop characteristics from the beginning.

With polymer, it’s also very easy to end up with a brittle material. It takes a lot of material research and understanding of mold design to avoid catastrophic damage in drops while avoiding creep, friction issues, chemical resistance issues, and other factors. It’s very easy to build a plastic box that fits in a magazine well, but it’s a lot easier to do that poorly than it is to do it well.

To be entirely fair, I’m not claiming that every metal, hybrid, and soft polymer AR-15 magazine that gets dropped becomes unserviceable—merely that the deflections that occur typically affect reliability numbers to a greater or lesser degree.

Due to the nearly infinite variables in drop and impact angles, a magazine that suffers deflection may become completely unusable. Or it might become a magazine that delivers only 30, 60 or 100 MRBS. Or, perhaps it the magazine might seem unaffected but still have significantly reduced overall reliability characteristics noticeable over a high round count evaluation of the damage.

Any reduction in pure TOP 03-02-045 test performance generally translates directly or even exponentially in a decrease in performance in dirty, dusty, cold, or other adverse conditions. An AR-15 magazine that was a 2,000 MRBS magazine before drop may become a 500 MRBS magazine after some damage. It may well go from being a 500 MRBS magazine to a 15 MRBS magazine in dusty conditions. That variability is what we wanted to avoid.

Decide What Matters to You

The bottom line is that there are plenty of AR-15 magazine construction options and plenty of philosophies on what is best and why. As a user, you have to decide what characteristics you care about. There is quite a bit of third party test data that is floating around with various levels of availability. Tests from a few years back pitted just about every commercial magazine available vs. various iterations of USGI and USGI EPM magazine and the GEN M3 PMAG. I’ve already mentioned the USMC data involving the EPM, Tan follower USGI, GEN M3 PMAG, and another commercial magazine. Much more testing was done with just the GEN M3 and GEN M3 Window and USGI EPM by US SOCOM and the US Army before full approvals for the PMAG GEN M3. Some searching can produce a lot of that data for your perusal in making your choices.

There are a lot of other things we could talk about concering AR-15 magazines. Interfaces with the rifle, reinforcement and sacrificial surfaces for drop characteristics, round constraint under recoil, follower contact areas, mold flow, chemical resistance…but I’ve already rambled on for too long.

I’ll leave it here for now and hope that this helps inform your decisions around magazine selection, whatever that selection may be. There’s a lot more to it than just being a box with a spring.

###

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: A lifelong firearms enthusiast, Duane started shooting and competing at a young age, and entered the industry with his first paid gunsmithing position at age 17. After earning a University Scholar’s Degree in Administration of Justice at Penn State University, where he served with University Park PD, Duane enlisted in the USMC as an infantryman. After an officer transition, Duane became an F/A-18 pilot with 112 combat missions in Iraq, earning 6 Air Medals, and also became a MARSOC plank owner with 2 ground combat tours to Afghanistan, on the second of which he earned the Bronze Star with Valor during a protracted battle in SW Afghanistan. After 12 years in the USMC, Duane rejoined the firearms industry with Brownells, and in 2012 joined Magpul, where he became Director of Product Management and Marketing, and is currently the Executive Vice President.

1 - 1Share

Yeah. I hear ya. I think all-polymer magazines are the absolute best, especially Magpul’s. But I run a SCAR 17. WHEN are you going to make a Magpul polymer magazine for my SCAR 17? No, I don’t want to hear about spending $500 for a lower that will accept (only) SR-25 PMAGs because I am NOT going to just throw out the 48 steel FN mags ($2000 worth) and then buy SR-25 PMAGs to replace them. What I want, and a lot of other people want, is a SCAR 17 pattern PMAG.