Mike Lewis is a 20-year Army infantry veteran, renowned for his expertise in small arms and doctrine development. His contributions to the “Professional Citizen Project” series, particularly CITIZEN MANUAL 3: AR PATTERN RIFLE AND CARBINE, have set a new standard in civilian firearm education.

This book is an indispensable resource for anyone looking to deepen their understanding of the AR platform—whether you’re a novice or an experienced shooter. By adapting military doctrine into practical, accessible guidance and building on it, Lewis ensures that every reader can gain the skills and knowledge needed to confidently own, maintain, and use an AR-pattern rifle. For those committed to the principles of responsible firearm ownership and preparedness, this is a must-have addition to your library.

Q: Can you share your background with those unfamiliar with your work?

Lewis: I am a 20-year infantry veteran of the Army with service in Korea, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Kuwait, and combat time in Iraq and Afghanistan. Most of my career was stationed on Fort Bragg (now Fort Liberty), with over half of it in the 82nd Airborne Division. Even though it was not an MTOE (Modified Table of Organization and Equipment) position, the 82nd Airborne had a small arms master gunner, which I was slotted as for the last few years of my career.

Q: How did your experience with the AR-15 and related rifles evolve over your career?

Lewis: I grew up shooting. My journey began as a child shooting at eight or nine years old, but my first exposure to the AR-15 platform was through the M16A1 during a Junior ROTC mini camp, and then again at a summer camp. After joining the Army in 1995, I used the M16A2 for the first three years of my career before transitioning to the M4 when my unit upgraded.

Over the years, I gained experience in the Army and in outside classes, ultimately collaborating in developing rifle training manuals like TC 3-22.9 and TC 3-20.40. These experiences shaped my understanding of AR-pattern rifles and their applications.

Q: How did these collaborations come about?

Lewis: Ash Hess contacted me when he was at Fort Benning, assigned to the doctrine office, and he was tasked with rewriting the rifle manual. He contacted me and a few others for collaboration and assistance in forming the wonderful draft that he had written into the finished book, TC 3-22.9 Rifle and Carbine.

When Ash retired, his replacement continued the effort of writing TC 3-20.40, the manual for individual weapons training and qualification. This manual covers the M4/M16, the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon in its automatic rifle role, pistols, and sniper rifles. I was honored to be included in this project, working alongside others who had contributed to TC 3-22.9. Theeffort produced a comprehensive guide for weapons training and qualification that remains a valuable resource.

Q: Can you tell us about Canebrake Consulting and your work post-retirement?

Lewis: After retiring, I founded Canebrake Consulting Services, LLC to provide training and education on firearms and training itself, as well as work with industry partners to produce training aids and material solutions.

Q: What inspired you to contribute to the “Professional Citizens Project” series?

Lewis: Jack Morris approached me in the spring of 2023 to develop a rifle manual for prepared citizens. The idea was to adapt military doctrine into “regular guy speak,” making it more digestible for civilians. I saw this as an opportunity to build on the work from military manuals like TC 3-22.9, incorporating insights specifically tailored to civilian applications, such as rifle selection, setup, and practical use.

I also liken the series to the “Foxfire” books of the 70s and 80s (a collection of History/Folk Wisdom from the Appalachians) —a tactical version for prepared citizens, focusing on skills that support the rule of law and align with constitutional principles.

Q: Can you elaborate further on the “Professional Citizens Project”?

Lewis: Jack Morris started the effort, looking specifically at the prepared citizens and skills that could be necessary for upholding the rule of law and the continuation of these great United States, and it could cover anything from using tactics, to survival, to land navigation, and it’s specifically looking at groups of citizens being professional citizens.

I see the series as a repository of knowledge aimed at prepared citizens. It covers self-defense, survival, and large-scale events, with the goal of supporting the rule of law under the Constitution. It’s designed to be accessible to both novices and experienced users, ensuring something for everyone without being too advanced or too basic.

Q: How did you approach writing your book, and were there any challenges?

Lewis: It took several months, much longer than I had initially hoped. The delay was largely due to the challenges I faced within myself. First, I had to overcome imposter syndrome. Second, I struggled with how to convey the knowledge I already had. All the information was in my head, but translating it into a usable format—one that could cater to both novice shooters and experienced professionals—was difficult.

How was I going to take all that information I had and relate it in a usable manner? I wanted it to be clear and digestible for beginners without being dismissive or insulting to experienced shooters. Parsing through all of this was a challenge, and I found it particularly difficult to take what was in my mind and put it onto paper.

I started by gathering several books I own—titles like Green Eyes and Black Rifles by Kyle Lamb, The AR-15/M16 Handbook by Mike Pannone, and others. However, I made a conscious decision not to read them while writing my own book. I didn’t want to be unduly influenced or risk inadvertently plagiarizing their work. Instead, I committed to relying solely on the knowledge and experience already in my head.

Q: What are some key takeaways from your book?

Lewis: The book begins with a critical chapter on firearms safety, as it’s essential for any application—whether recreational, hunting, or defensive. From there, it addresses and debunks common myths about the AR-15, such as the misconceptions that it’s overly maintenance-intensive or that the 5.56 cartridge is only suitable as a varmint load.

The book also provides technical insights, guidance on selecting and setting up rifles and ammunition, and introduces a refined shot process that emphasizes a holistic approach to weapons handling and target engagement. Additionally, it includes baseline performance standards, such as achieving consistent four-minute-of-angle (MOA) groups and accurate range determination.

The content flows naturally from technical data into rifle operation, then into the details of selecting a rifle or individual parts. It covers ammunition and ballistics, including terminal ballistics with demonstrated examples, before transitioning into setting up your gear. The shot process section offers a deeper level of understanding, breaking down its elements in a clear and practical way.

From there, it discusses zeroing the weapon and establishes very basic performance standards that I believe every armed citizen with an AR-15 should meet. These standards are intentionally kept at a baseline level, representing the minimum level of competence and not a high-performance benchmark. The focus is on ensuring practical, attainable skills for responsible firearm use.

Q: What is that baseline?

Lewis: For example, my standard is a four-minute-of-angle grouping. One minute of angle is approximately one inch at 100 yards and serves as a measure—not a linear measurement but an angular one that translates to a linear measurement at distance. If you can hold a four-minute-of-angle group, it equates to roughly four inches at 100 yards and about 20 inches at 500 yards. If you can consistently maintain that grouping, you can successfully engage targets—depending on target size—assuming you use the proper hold- adjusted point of aim- or the correct sight correction for the given distance, out to 500 yards.

Additionally, there are standards for range determination. Personally, I believe a good standard is being able to estimate range within 10%. For instance, at 500 yards, you should be able to determine the range as 500 yards ±50. At 400 yards, the range should be determined as 400 yards ±40. This level of accuracy is important because it directly impacts ballistics and trajectory.

Q: A lot of times, people buy a rifle without really knowing what they’re doing. They get to a range—maybe a bench rest range—and start practicing. What are the biggest mistakes people make? Is there one key piece of advice, or is it more complex than that?

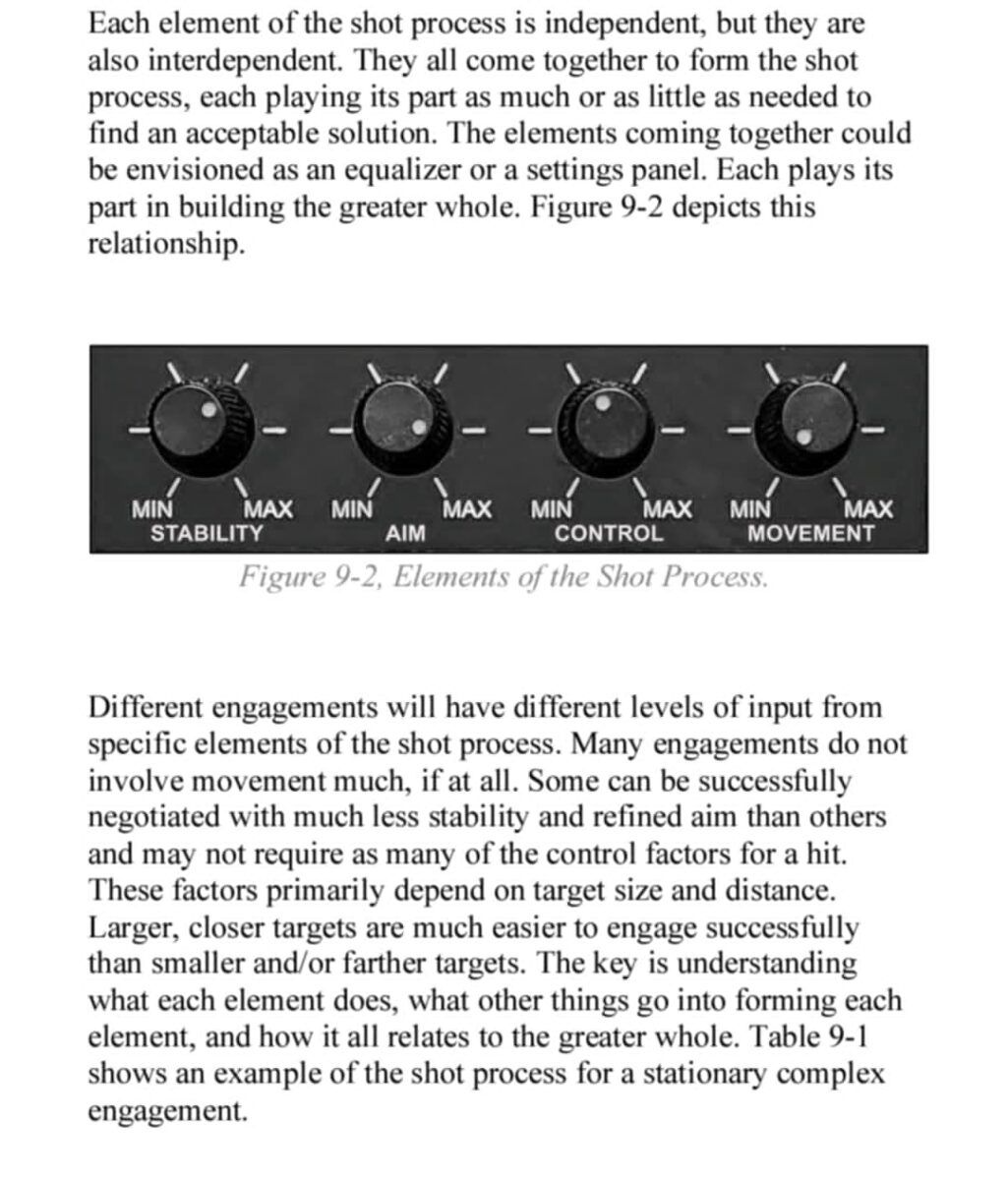

Lewis: While I don’t believe anyone should be required to seek training, it’s a personal responsibility that we, as armed citizens, should take upon ourselves to seek proper guidance and education. That said, the two biggest mistakes I often see with the shot process are related to stability and aim, which are the first two elements of the shot process.

Stability sets the tone for everything else. You don’t necessarily need to be motionless. You need to stabilize your rifle well enough that your sights can settle on the target, even if there’s some movement. That movement should remain within an area that still allows for an acceptable hit.

Aiming is the second most common error that I see. However, if you can build a stable firing position and achieve good aim, you’re already halfway there. Focusing on just these two elements can significantly improve your shooting performance.

Q: One myth you address is the idea that AR-15s are like Legos. Can you elaborate?

Lewis: This concept, popularized by the late Will Larson, emphasizes that AR-15s are not like Legos. Parts from different manufacturers can have variations in coatings, materials, or dimensions, leading to potential compatibility issues. For those without proper training, tools, or experience, assembling a rifle for defensive use is risky. I advise most people to buy a complete rifle to ensure reliability, with the reasoning covered in the book.

Q: Why is inspection an important part of AR maintenance?

Lewis: Cleaning the AR is not as critical as it was during the days of corrosive ammunition, but regular inspection is vital. Cleaning allows you to identify wear, damage, or other issues that might require part replacement. Cleaning should focus on removing debris and rust rather than obsessing over carbon buildup, which rarely impacts functionality. Detailed cleaning also enables a thorough inspection of key components for signs of wear. Inspection allows identification of parts nearing their end of service life, enabling the user to keep the rifle in proper operating condition.

Q: How do you stay current with trends and best practices in firearms?

Lewis: Through training, competition, and observing others. Competition validates training and setups while revealing gaps to address. I particularly enjoy competing with Quantified Performance, which focuses on weapons proficiency. Quantified Performance. is well-aligned with the designated marksman role and has been invaluable for testing setups and exploring new techniques.

To be clear, I don’t see competition as training. I see it as an opportunity to validate prior training, test your setup, and identify any gaps in your skills or equipment. From there, you can adjust your setup and train to address those gaps.

In competitions, I encounter a wide variety of rifle configurations and see shooters using them in generally consistent ways, but occasionally with unique techniques or setups. Some of these are interesting and spark ideas—either as something worth trying or something that clearly doesn’t work. I often try these concepts myself to confirm their effectiveness. Of course, beyond competition, training and taking classes are essential for continued growth and improvement.

Q: What should people consider when setting up their rifle?

Lewis: I think the key is to set the rifle to yourself, including adjusting the collapsible buttstock and mounting the optic with proper eye relief. Decide on accessories based on your application—for instance, a light for defense or a bipod for precision shooting. Avoid copying others’ setups without understanding their purpose; tailor your rifle to your specific needs. What works perfectly for one scenario might be completely unsuitable for another. That’s why it’s important to tailor your setup to your specific needs.

You also need to set up your optics correctly. One area I focused on in the book is mounting and leveling optics. There’s a lot of tribal knowledge around this topic—shared online or in person—but I wanted to codify what I’ve learned into a clear, structured method. The book details how to mount and level an optic properly, how to achieve correct eye relief, and how to fit the rifle to yourself.

When mounting an optic, you first adjust the rifle for length of pull to fit your body, then position the optic to achieve the proper eye relief. Different optics have different eye relief requirements, so it’s important to get this step right to ensure optimal performance and comfort.

Q: What’s your advice for someone setting up a general-purpose AR for home defense?

Lewis: For a defensive rifle, a light is absolutely necessary. When it comes to optics, the choice between a red dot and a magnified optic depends on your needs. If you opt for a magnified optic, you’ll need to decide whether a low-power variable optic (LPVO) or a higher-magnification option better suits your purpose. Ultimately, every choice—whether it’s accessories, optics, or setup—should be guided by how you intend to use the rifle.

That said, a sling is non-negotiable. The bottom line for me is that for a general-purpose rifle, I tend to recommend a 16-inch barrel, a light for low-light situations, and an LPVO for its etched reticle and magnification range. LPVOs enable the user to see better and allow for better aim refinement compared to red dots or magnifiers, especially when holds are required.

Q: Where can people go to get a copy?

Lewis: CM3 and other great reference materials are available at https://tpcproject.com/collections/references.