Simple mistakes, mental mistakes, and bad gear choices may be holding you back from becoming a better shooter and a more capable armed citizen. To learn simple, practical areas where we can improve, we recently reached out to Mark Smith of JBS Training Group. We discuss a new course he’s working on, concerning trends, common gear mistakes, and more.

Be sure to check out recent articles we’ve done with Mark Smith below:

- JBS Training Group Talks New Courses and Overcoming the Static Range Mindset

- Mark Smith of JBS Training Group Talks Rifle Support Bags

- Mark Smith of JBS Training Group – Range Mindset & Training the Individual

- In Defense of the Red Dot Optic with Mark Smith

- High Scope Mounts on the AR-15 – A Q&A with Mark Smith

- LPVO Basics – Mark Smith On Low Power Variable Optics, Part 1 – Reticle Selection

- LPVO Basics Part 2 – Mark Smith on Magnification, Mounts, and Focal Plane

- Mark Smith of JBS Training Group – Best LPVO Setup and Considerations

- LPVO Basics Part 3 – Mark Smith on the Zeroing Process

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – Most people don’t understand medical enough to know how to be prepared. It’s almost like people treat medical gear like they do back up iron sights on a rifle. They just throw them on there because they do not want to be made fun of, and the internet says they should have them. I see tons of guys that, if they have medical, they only have a tourniquet. The problem is that it only works for appendages. Arms and legs are not all that we are made of.

I recently made a med kit with North American Rescue that helps cover all bases, even as a layman. It has a tourniquet, wound pack, trauma dressing for that wound pack, a double set of chest seals, two pairs of gloves, trauma shears, a Sharpie, a shock blanket, and an instruction card that gives detailed pictured instructions on how to apply this stuff in the event you don’t know how or if you’re in a mini-panic and you forget. It’s all vacuum-sealed and packaged up, and you can carry it in the console of your vehicle or somewhere else. My thought with this is that if you have the mindset to want to help people, then you’ve got to be ready to do that. It’s deeper than just getting a concealed weapons permit and shoving a gun down your pants.

I believe there are things in this life that would be worse than death if they were to come to fruition. I don’t want to die, but you’re not going to scare me with that. I fear living through failure. I can’t imagine someone having to live the rest of his life after watching someone bleed to death on the side of the road, not because he couldn’t do anything about it, but because he chose not to be ready to. I can’t live like that, so I will not.

This has led me to a new course for the responsibly armed citizen I am working on that’s about more than shooting. It’s about responsibility for those who intend to offer assistance to others. We’ll explore the risks involved in doing so and how to mitigate those risks based on the student’s stated life mission parameters.

These are the things that I think are important, as well as determining “what is your line of violence?” Everyone has a line, even if they think they don’t. Everyone will fight, but will they fight in time? Some people won’t fight until they are lying there bleeding to death, and it’s an instinctual, primal reaction. Where will you fight? How does the context of the situation affect that line?

Q: Let’s talk about some of your other courses. I’ve heard there have been a few tweaks here and there.

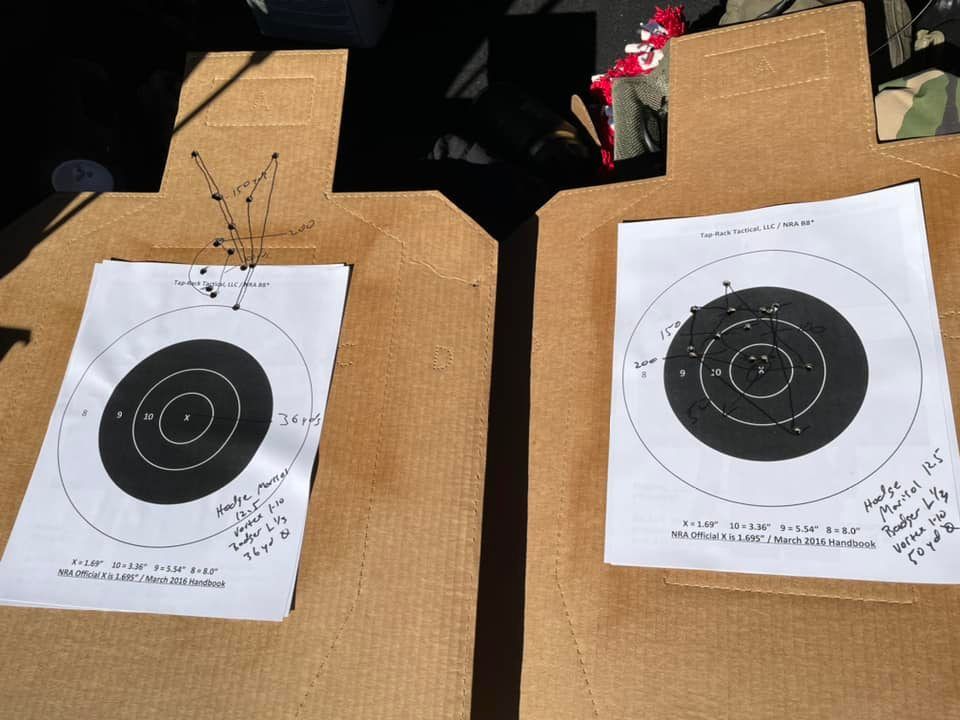

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – My rifle courses have morphed unintentionally. I’m trying to make rifleman, man. I find that dudes are so tuned up to having all this Gucci stuff and super-fast reload crap, yet they cannot hit what they are aiming at. That is the main mission here and the reason the gun was produced – so that when you fire a shot and you hit your target. If you can’t do that, I’m not impressed with what else you can do. (laughs).

There are a few concerning trends that I see. The first one is the lack of understanding of the entire picture concerning safe weapons handling in an environment that is outside what you might typically encounter. I feel that most shooters are brought up and shaped in what I call a safe environment. These are places where it is almost impossible to have a safety problem because the guy running the range doesn’t want anyone getting hurt on his range, insurance parameters, and all those other things. It’s an environment where it is almost impossible to have a problem. The issue is that you never expose a shooter to a place where things could go wrong, should he allow them to.

I see students’ eyes light up during my morning safety brief. I have to remind them that I will not be putting them in a situation where they are in front of another man’s gun and have bullets slinging by them because they need that or something foolish like that (laughs). Still, I intend to put you in an environment that causes you to need to stay switched on the entire time, or we will have a problem.

I will have you moving up-range, down-range, side-range, and all over the place, forcing you to think about what’s happening in the world around you. I want you to understand that you are not the most important thing out here, understand your responsibility, taking care of the men around you, and know that no one cares about your excuses. The reason I do that is I think it is good brain food. I think it’s good not to be scared of that.

Q: Moving on, recently, you mentioned something that had me removing some things off one of my rifles. Can you dive into that?

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – The next trend I see on the rifle side of the house is how many shooters have crap hanging off their guns that is more of a detriment than an asset. It’s not so much ‘do you need it?’ but is that thing benefiting you in the 90-percent realm? Meaning, 90 percent of the time, does that thing come in handy? If the answer is no, I will implore you to consider why you have it on there. Shooters will tell me that it is something that they had lying around and wanted to use, or they saw some guy’s gun that had it and thought it looked cool.

Q: When you’re new, it can seem like you should just copy what everyone else is doing, without questioning why they are doing it, right?

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – The biggest problem in the gun industry has always been that we have a hard time seeing life through other people’s eyes. We have difficulty seeing that someone else’s parameters and context may differ. The fact that he has it on his gun does not equate to you needing to put it on yours. I find students struggling due to things on their gun that they thought would make things easier but actually make them hard.

The other side is, can they even use the things they have added? I can’t tell you how many guys I see with conventional 12-o’clock iron sights on their rifles paired with a bolt-on scope mount. Are they carrying an adjustable crescent wrench in their dump pouch in case they need to get that thing off there (laughs)? If not, why do you even have iron sights on the gun? What about using offset irons instead or something that makes more sense?

The other side relates to some data collection I have done in my courses. Over 80 percent of the people who have iron sights on the gun say that they are not zeroed. If they are not zero’d, then really, why do they have them on there? I am not advocating that you should not have iron sights. I am simply saying that if you have them, you should be able to use them.

Lasers…visible lasers on the front of the gun. I see many guys with them telling me they are their backup aiming system. I will then ask them to use it at high noon at 100 yards away, and they literally can’t see it. Even if it’s just a nighttime setup, more often than not, it is not zero’d. If it is zero’d, it’s been done at an improper distance.

You also need to think about the things that you have hanging off the 6 o’clock of your rail. Do I actually need that thing for recoil? The answer often is that it does not help with recoil mitigation, so you’re left with something that is now very good at getting in the way of barricaded shooting or going prone on certain things.

Knight’s Armament makes a barricade stop, which is attached via M-Lock, and its purpose is so that you can drive the stop into a barricade, and it provides some stability there. I’ve found that these often get in the way. There are also certain things that tend to get hung up on kits and pants. I saw a guy rip a hole in his pants with one.

The index stops are also getting hung up on everything. We find those get hung up on clothing, gear, slings, and barricades. It’s not that they are not applicable for a person; rather that I think they are not applicable for most persons. It is a risk versus reward paradigm where you have to think about ‘where is this usable?’ and whether this ‘being on your gun is going to be the difference between a hit or a miss?’ If the answer is ‘no’ then the good news for you is that you get to have a lighter gun. Take that thing off of there.

Too often, I see that guys allow this gear to decide for them the way that they run a gun, meaning it is not uncommon to see vertical grips and things of that nature in our rifle class. When we go through the recoil portion, we start to change how we hold the gun and how our bodies are connected to the gun. Guys will struggle because they don’t want to let that grip go. I have to remind them that those things move, and they can put them wherever they want, and you don’t need it telling you what to do. I wonder how many people out there will read this article who are struggling through shooting because of gear they have that they don’t need.

Another thing is that in 2022, I think there is a trend to see who can make the highest red dot mount. I see many guys taking the optic heights higher and higher without taking the cheek risers up with them. People still don’t understand the relationship between the human interface and the machine, and they do not know how big of a deal the cheek weld is. This is often because they have not yet been in an environment where accuracy and precision become a thing. Does it matter for 10-yard A-zones? No, not at all.

Q: Can you explain the height you need to get a riser for your stock?

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – There is no one-size-fits-all answer for this. It is all based on human facial structure and interface to the gun. Many people would benefit from running a little ¼” riser even on a standard 1.54” mount based on their face structure alone. When I shoot these precision gas gun matches, it is not uncommon to see me with a ¼” riser on a Magpul CTR stock with a 1.54” mount because of how tight I will get into that gun for those shots.

An easy way to test it is if you get on a gun and let your entire head weight rest on the stock and open your eyes. If you have submarined below the optic line, meaning you see a shadow come into the scope from the bottom; that indicates that you need to go up with a cheek riser. How far up is typically based on how far up you brought the optic…For these higher mounts like 1.93, 2.04, and even higher than that, my cheek riser will look like a stack of books in a corner. If you don’t have that, you have a floating head. You are no longer connected to the gun, and it prevents you from getting on the gun the exact same way every time. Precision is all about consistency. I am not smart enough to get into the science of biology, eyeballs, light bending, and all this other stuff, but I can tell you that it is detrimental not to have it.

Q: This does not apply to all ARs, though…the Honey Badger, for instance. It seems like that would be impossible to put a riser on.

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – The other side of it is discerning ‘do I need this?’ The Honey Badger is a tiny gun not made to shoot sub-MOA groups at 100 yards. It was made to be small and deployable. The guy with the Honey Badger is probably not concerned with hitting a small circle from 100 yards away. If he was, would he go prone to do it? My guess is ‘no,’ and he would be shooting it almost exclusively standing.

It’s not that everyone needs to do this, but if you are taking your optic and throwing it up 2” above a conventional setting and you have not considered that every time you mount the gun, your head is in a different position, you will struggle at shooting precise groupings at the same spot every time. It’s not uncommon to see your group shift…upwards of 2-3” inches at 50 yards away just because you cannot get on your gun the same way.

So, does everyone need to have a riser? No. But if you are struggling to shoot precisely, and especially if you are struggling to hit at a distance beyond 200 yards, you may want to consider that you may have a parallax issue going on or a ‘consistency behind the gun’ issue going on because you don’t have a cheek weld. Instead, you have more of a ‘neck/chin weld’ that is not conducive to precision.

I do want to be clear that I am not a tall mount hater, but I believe that going to a tall mount should solve a problem that you have. If it does not, it is probably creating problems you didn’t have. The feel-good answer you hear is that ‘oh, I like a more heads-up position, and it reduces my neck strain.’ OK, well, so what? Explain to me how that makes you a better overall shooter. Is it solving a problem? Explain it to me because you cannot just say that. You have to explain to me how it is beneficial. If you can’t do that, then I think you might want to reconsider.

Q: Any other concerning trends you’re seeing?

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – The last one is people that have self-justified their accuracy mediocrity. They are attempting to make themselves feel better about not being able to hit stuff by creating fantasies in their head where what they can do is ‘good enough.’ Now, I’m not here to tell you that it’s not, because I don’t know what that will look like on that day. But, I will tell you that ‘good enough’ is only good enough until it ain’t. That’s the environment that I am concerned with.

The other side of it is what is detrimental about striving for perfection? I can’t find anything wrong with that desire. What is detrimental about knowing your bullet’s flight path exactly out to 300 yards and having a perfect zero? Knowing what a perfect shot feels like…knowing what parameters must be met to create a perfect shot. What’s detrimental about that? I can’t find it. You got the gun out because you wanted to hit what you were aiming at. If you are not doing that, your fast reload does not impress me. That’s not going to help me. I need you to hit. If you don’t know how to hit, you are essentially useless.

Q: Can you remind readers of some of the fundamentals they need to know to make those hits?

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – It’s not that they can’t do it. It’s that they don’t choose it. Often, people miss because they are concerned with results and outcomes and with time. I always say, ‘I can make you fast very easily,’ but I cannot make you choose to hit the target. That’s a choice that you have to make. If you care about hitting that target more than anything else in the world – more than time, more than if you are going to beat your buddy – you will hit it.

Q: Anything else you’d like to add?

Mark Smith – JBS Training Group – Guys will always come up to me after class and ask what the one thing that they need to work on is. Almost always, my advice for them is to ‘touch the gun every day.’ They need to get more comfortable with the gun in their hand, using it, manipulating it, shouldering it, reloading it, loading it. So many deficiencies that people have could be ironed out if they would take the time to touch their gun every day. Get that thing in your hands, and, as we’ve covered, make sure that what’s in your hands is tailored for you, not someone else.

###

1 - 1Share